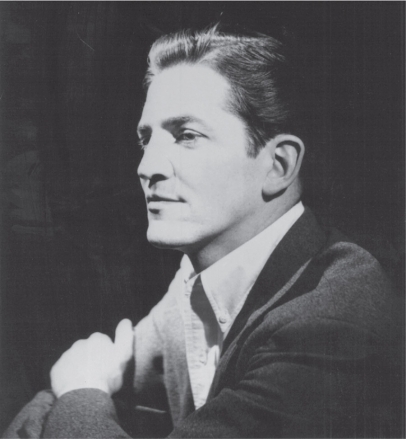

Mid-Century Modern Craftsman John Prip

A Master Silversmith for a Modern Age

There was a time in the mid-1940s and ’50s when brides selected their silver service from fussy and derivative designs. Then came John Prip, a master metalsmith, designer-craftsman and teacher who brought elegant and organic forms to the dinner tables of mid-century consumers. And amazingly, this creative artist was able to adapt his avant-garde designs to the requirements of the commercial production process.

Sixty years after he designed it for Reed & Barton, Dimension, his onion-shaped tea and coffee service in silver plate, is a classic—on display at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The round-bodied vessel curves smoothly into its cover, ending with a pencil-slim point and topped with an ebony knob. The raffia-wrapped handle echoes the shape of the pot. It is an object that begs to be touched and today a complete service can sell for several thousand dollars when one comes up for auction.

John Prip was a fourth-generation silversmith. He was born in New York City in 1922 and, as a child, moved to Denmark, where his father took over the operation of the family silversmith factory. He acquired technical skills as a teenage apprentice with renowned silversmith Evald Nielson of Copenhagen but was able to push beyond the classical forms he learned there to develop innovative modern designs.

When he returned to the United States in 1948, Prip joined the faculty at the School for American Craftsmen in Alfred, NY. (The school soon relocated to the Rochester Institute of Technology where Prip followed.) In 1960, he joined the firm of Reed & Barton in Taunton, MA, with the title of artist-craftsman-in-residence. It was understood that he would make drawings, models and prototypes for mass-market production by the firm’s 900 workers, but there were no restrictions on his designs.

Working in a private studio at Reed & Barton, he was able to successfully bridge the divide between the worlds of craft and industry. Factory-made pieces like Connoisseur, a glazed earthenware and silver plate casserole; his sterling silver flatware patterns like Lark and Dimension; and his color-glazed serving bowls were advertised “for the young and aware.” Now, they are highly sought after by devotees of mid-century design when they come up for auction, says Elizabeth Williams, curator of decorative arts at the RISD Museum.

“He lived in that world and was very successful in it,” says his son Peter Prip, senior critic and adjunct professor in the industrial design department at RISD. “No one had that skill set at the time. He was able to communicate with everyone in the factory.”

John Prip came to RISD in 1965 and began teaching in a basement workroom with a handful of students. When he retired in 1981, his metalsmith department was recognized as one of the best in the country. His students were like family, recalls Peter. There were student parties in his home and John maintained relationships with many of his students long after they left RISD. “Both my parents were very generous with their time.”

He sometimes went back to the classroom after hours and rearranged students’ work, taking elements from one novice designer and attaching them to the work of another. He wanted to show them how to develop concepts, to be flexible in their design process. He also gave detailed demonstrations and deconstructed each step to make the process understandable. Peter describes his father as a very shy and modest man. “He was not very verbal but he was a wonderfully important presence. And he had very high standards.” Peter continues, “He couldn’t balance a checkbook but he was unbelievably disciplined in the studio. He would work on four to eight things at the same time and, to the untrained eye, it all looked chaotic, but he knew exactly where everything was.”

“His studio pieces were more complex and had a higher level of detail,” says Williams. They were done in sterling silver, often with a touch of whimsy, like the bird pitcher with an ebony handle. Peter says his father’s studio work was more lyrical and experimental. He did not take commission work and had no gallery affiliations. “His great pleasure was in the making of things,” says Peter. “He created for his own pleasure. It was his obsession, his life.”

His work for Reed & Barton and teaching at RISD allowed him that luxury, though Peter remembers that when his father taught at the Rochester Institute of Technology, he traded some of his creations for dental services. “Dr. Wadsworth’s family probably has some of my father’s pieces.”

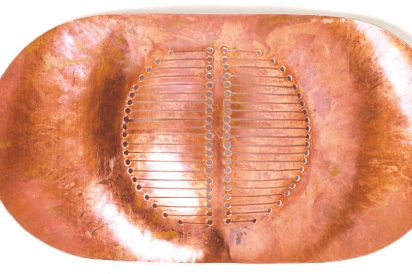

Silver is an extremely malleable metal; it can be hammered, cast, chased, cut, spun or drawn into a hair-fine wire. Prip worked out his designs in a three-step process (an excellent example is on display in the RISD Museum). He would begin with a sketch, then he folded paper, origami-style, into the shape he wanted to create, playing with variations and possibilities. He would then transfer the pattern to a malleable metal like thin-gauge roofing copper and finally into silver.

His work for Reed & Barton was meticulous and he produced options for every design. He understood the pragmatic requirements of creating silverware for a mass market. “It is easily evaluated,” he explained in a 1964 interview with Craft Horizons. “It shows up either in black ink or red ink.”

Today, few betrothed couples put silver flatware on their list of musthaves. “Polishing the silver” is as passé as watching television on a black-and-white TV. Lifestyle changes—dual working parents and single-parent families, a lack of time and household help, more casual entertaining and frequent restaurant dining—have, sadly, pushed silverware into attic storage. But even if just placed on a shelf, the silverware pieces designed by John Prip should be admired as stunning works of art.