The Enduring Elegance of Gorham Silver

Made in Rhode Island and Admired Around the Globe

After a visit to the RISD Museum in Providence, you may never look at your own forks and spoons the same way again. The museum’s collection of fine tableware will make you pause to think how the simple act of eating led to designs that elevated the ordinary and inspired the extraordinary. The museum holds in its collection many particularly remarkable sterling silver pieces for the table made by Rhode Island’s Gorham Manufacturing Company. Perhaps no company in the world extended the influence of tableware design more than Gorham, founded in Providence in 1831. From a small silversmith shop that began by making handcrafted teaspoons, Gorham grew to become the world’s leading manufacturer in tableware design and production in its heyday.

Made by Hand

Back in Rhode Island’s Colonial days, few people were wealthy enough to enjoy the aesthetic or conductive benefits of silver flatware. A single spoon was worth two days’ wages. The small market was supplied by overseas imports and, beginning around the 1690s, a handful of talented Newport silversmiths turned out tankards, creamers, porringers and spoons.

The market grew with Rhode Island’s economy, fueled by West Indian trade, privateering and slave trade profits. By 1831, when master silversmith Jabez Gorham partnered with Henry L. Webster to manufacture coin silver spoons in Providence, demand had grown for quality, locally made silver pieces.

“Coin silver” is just what it sounds like: Because silver was a scarce commodity (a steady source of American silver wouldn’t be discovered until 1858), silver coins were melted down and used to make other silver objects. This wasn’t a simple matter of drizzling molten silver into a mold, either. Each spoon was individually handcrafted. As such, no two of these early wares are identical.

A Growing Market

As it grew, Gorham Manufacturing catered mainly to the wealthy and the influential with its fine silver products. You might ask, “Why silver?” Former Gorham Marketing Manager Rob Schmidt says, “Sterling is a warmer metal that conducts temperature more readily than stainless steel, so the warmth or coldness of the food you bring to your lips is more accurately reflected in sterling spoons or forks. Take ice cream—the spoon immediately gets icy, just like the ice cream.”

Studies have shown that attractive environmental elements, too, can affect our taste buds, making us believe food tastes better than it would if eaten with unadorned utensils. Simply put, sterling silver can enhance your dining experience.

Gorham’s first silver spoons were a pattern known as Fiddle, a common design in the Colonies at the time, with a narrow shoulder, narrower stem and a wider, slightly tapered handle. Tipt and French Tipt designs followed around 1840 and 1845, both featuring variations on Fiddle, but with a raised terminal shaped like a widow’s peak.

Business Expansion

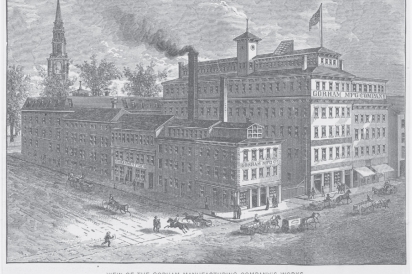

Gorham’s original factory was located at 12 Steeple St. in Providence. Jabez Gorham built a profitable business, but when he retired in 1847, his son John took over and, by investing in labor, talent and technology, grew the company into the largest of its kind in the world.

Between 1853 and 1854, the company acquired its first steam-powered drop press, a machine that allowed for the mass production of flatware pieces. No longer did each piece need to be handcrafted from scratch, although a significant amount of work still remained for chasers, finishers and polishers. As well, the press allowed for a move away from simple utilitarianism to elaborate flights of design fancy.

A pair of pieces from around 1885 is an excellent example of the height of the Gorham silversmith’s art—the Narragansett salad serving set. The cast set was designed so the bowl of the spoon clearly resembles an oyster shell and the tines of the three-pronged fork are reminiscent of Neptune’s trident. The handles of both are wrapped and encrusted with delicately sculpted crabs, fish, shells, seaweed and barnacles, and each handle terminates in a small clam or quahog shell. They each measure just under a foot in length.

By 1890, the Steeple Street location had grown to cover the whole block bounded by Canal, Steeple and North Main streets.

Needing yet more space, the company moved to a larger complex beside Mashapaug Pond in South Providence, served by its own railroad spur.

On-site amenities on the new campus included a dining hall and “casino”—an event space for employees and their families. In 1930, Gorham employed more than 2,000 men and women.

A Design for Every Taste

Gorham’s most popular flatware patterns were designed by William Christmas Codman, an Englishman hired in 1891 to head up the design department. From his designs came the patterns Strasbourg (1897), Buttercup (1899), Old French (1904), Fairfax (1910) and Chantilly (1895), the single most popular silverware pattern ever.

It’s hard to say what makes Chantilly so popular. Bill Barol, writing in American Heritage Magazine in 1989, noted it was “neither the plainest nor the fanciest ever made by the Gorham Company,” and theorized, “Perhaps it is this balance between abundance and austerity that explains the overwhelming success of Chantilly.” The pattern’s curves are elegant and voluptuous, without being overstated. Popular enough upon its release, Chantilly had a resurgence in the 1920s, perhaps in a reaction against modernism, and its regard hasn’t significantly waned since. President George W. and Laura Bush chose Chantilly flatware for Air Force One.

Burr Sebring, design director at Gorham from 1958 to 1981, explained that the company would conduct “flatware surveys” twice a year, traveling around the country with a collection of silverware patterns—some old, some new—to get the opinions of various groups on what patterns they liked best. Interestingly, different regions of the U.S. preferred different styles. “The southern parts of the country were interested in a more ornate decorative pattern,” he said, “whereas the Northeast preferred a plain or contemporary design.”

Well Beyond Cutlery

Gorham designed and manufactured much more than just silverware. Anything you can think of that could be made from silver, they made. Tureens, pitchers, coffee pots, platters, candlesticks, centerpieces, snuff boxes, thimbles and handles and trim for hand mirrors, brushes and combs.

Gorham had a library of more than 1,000 books (now held by RISD’s Fleet Library special collections) containing drawings and photographs of every conceivable design element or style, both natural and manmade, from around the world. These volumes helped designers get just the right look for a dragonfly’s wing, a particular type of seaweed or the bark of a tree. Gorham’s extensive creations in a variety of styles owe a great deal to these books.

Some of Gorham’s most celebrated works include:

• A beautiful seven-piece silver tea set given to Mary Todd Lincoln by “the citizens of New York” for use in the White House (1859).

• The Furber Collection, an 816-piece set of silver commissioned by Henry Jewett Furber, president of Universal Life Insurance Company of New York, between 1873 and 1879, all of which are now owned by the RISD Museum. The dishes, utensils and decorative items were enough to serve 24 diners.

• The bronze Independent Man statue atop the Rhode Island State House dome (1899).

• A writing table and chair (in the collection of the RISD Museum): Designed by William Christmas Codman for the 1904 World’s Fair, these items required 10,000 man-hours to complete and contain 47.5 pounds of silver.

• An elaborate silver tea service for the battleship USS Rhode Island (1907), now displayed at the John Brown House, on loan to the Rhode Island Historical Society. Gorham produced similar services for several of the other state-named battleships in the U.S. fleet.

• The Borg-Warner Trophy (1936), presented to the annual winner of the Indianapolis 500.

Final Curtain

Two of the last few silverware patterns designed by Gorham—Newport Scroll (1983) and Sea Sculpture (1986)—are decidedly very much of their time. Their clean and chunky lines would not be out of place in any John Hughes movie, alongside shoulder pads and angular haircuts.

But Edgemont (1987), which may be the very last Gorham silver pattern, harkens back to an earlier time. Its fluted stem and handle, with elongated scallop on the terminal, is very similar to Late Georgian (1934). So similar, you’d be tempted to say they’re the same. And they may be, as author Charles H. Carpenter Jr. noted in his 1981 history Gorham Silver, 1831–1981: “The changing of flatware names seems to have been a never-ending process since the 1850s.” Some call Edgemont a remastered edition of Late Georgian, a greatest hit trotted out for a final bow.

Gorham Manufacturing Company, once the biggest silver manufacturer in the world, is no longer. By the time Gorham effectively ceased to be a discrete business entity (after a series of corporate transactions beginning in 1967), it had produced more than 300 different silverware patterns.

Many of those patterns live on, for sale to the public by Lifetime Sterling and on websites specializing in the replacement of lost or damaged pieces, where a single teaspoon sells for $35. To be sure of its authenticity, look for Gorham’s signature imprint of a lion (representing silver), an anchor (for Rhode Island) and the letter G (for Gorham).

You can otherwise enjoy Gorham’s unparalleled artistry—including silverware, serving and presentation pieces—at the RISD Museum’s 2019 show: Gorham Silver: Designing Brilliance, 1850–1970 in which the famed Furber Collection will be on display.

The RISD Museum will host an extensive exhibition showcasing the works of one of Rhode Island’s most celebrated design and manufacturing firms when Gorham Silver: Designing Brilliance, 1850–1970 opens in May 2019.

The show is set to run from May 3 to December 1, 2019.