Foodways to Freedom Through the Kitchen

African Americans in Rhode Island Who Used Food to Achieve Independence

A mong the gifts that immigrants have brought to the United States are their native cuisines. Indeed, opening a restaurant or food-related business was—and still is—a traditional recipe for financial success for first-generation Americans. And we’ve become a nation of foodies, nourished by dishes that reflect cuisines around the world, from the rustic to the most sophisticated.

Culinary skills bought freedom for African Americans who came to Rhode Island as slaves, but the route was longer and harder. At a June program in the “RelishingRI” series—a year-long celebration of our state’s foodways sponsored by the Rhode Island Historical Society—historian Keith Stokes told the story of enslaved Africans who used their cooking and entrepreneurial talents to build productive and independent lives.

“It was creative survival,” said Stokes, who is vice president of the 1696 Heritage Group, a consulting firm dedicated to helping persons and institutions increase their knowledge of ethnic and racial history of early America.

“These individuals were brought here in the worst of circumstances and in a relatively short time were able to build a better life. They parlayed their food skills to earn a wage and to transport themselves from slavery to freedom.”

Between 1705 and 1809 Rhode Island merchants sponsored more than a thousand slave-trade voyages, bringing Africans to Rhode Island to work for the first families of Providence and Newport and the plantations of South County. They were referred to as servants instead of the distasteful description of slave. “But they were enslaved as chattel property,” says Stokes.

Once here they were trained to do the skilled jobs their owners required of them as barrel makers, stone masons, carpenters. Household servants learned to cook and serve food to their wealthy families.

Despite the “mammy” caricature of a jolly black woman wearing a bandana while cooking up mouthwatering meals, the Rhode Island women (and men) who cooked in other people’s kitchens were smart, strong and talented. In The Jemima Code (University of Texas Press, 2015), author Toni Tipton Martin notes that these men and women must have “possessed sales and presentation skills in addition to their cooking ability. We can assume that these practices included persuasive speaking, developing a good sales pitch, motivating and inspiring customers to buy, speaking with authority, managing inventory and pricing goods.” Tipton Martin is describing Southern blacks who, after abolition, earned money for their culinary talent. The same skills applied to Rhode Island’s black chefs, beginning in the 18th century.

Duchess Quamino was a cook in the Newport household of William Ellery Channing, a Unitarian preacher from a distinguished family. Quamino was born in 1753, possibly in Senegal or Ghana. She was famous for her baking skills and her frosted plum cake was the finest of its time, said Stokes. While running a catering business from the Channing home, she served her cakes to George Washington on two occasions. Eventually she opened a takeout bakery in a space that is now a parking lot on Mary Street in Newport. With the money she earned as “the pastry queen of Rhode Island” Duchess Quamino was able to purchase her freedom and that of her children.

Elleanor Eldridge was born in Providence in 1784 to an African father and an Indian mother. As a dairy maid in a Warwick household, Eldridge made bread and cheese. Unlike the South where cotton and tobacco were cash crops, Rhode Island had to add value to its natural resources by turning them into salable products. Cheeses from South County farms, for example, were cured in salt air, which gave them a unique flavor. In a state with hundreds of dairy farms, Eldridge became a renowned cheesemaker who produced 4,000 to 5,000 pounds annually.

An industrious worker, she considered marriage an unnecessary distraction. She was reputed to have stated, “While my young mistress courted and married, I knit five pairs of stockings.” Eventually Eldridge was able to buy a house in Warwick and another in Providence—a notable achievement for any woman at the time but especially one of color. Her story was told by Frances Whipple Greene in The Memories of Elleanor Eldridge, written in 1838. The Rhode Island Historical Society owns a copy of this poignant memoir.

How did they earn money to buy their way out of forced labor? In deeply religious New England, Sunday was a day of rest and worship, even for enslaved Africans. But by choosing to work for themselves on what should have been a day of respite from their daily chores, many African heritage servants were able to earn their own money. Often they were leased out by their owners to work for other people and were permitted to keep a portion of the money they earned.

Taking a crop from its raw state to a useful product enabled Obadiah Brown, Prince Updike and Abraham Casey to move from slavery to free men. The three were master chocolate grinders who were paid a wage if they produced more chocolate than required. Updike was able to grind 2,500 pounds of cocoa into 2,000 pounds of chocolate. Brown, Updike and Casey sold their excess chocolate to Aaron Lopez, a manufacturer whose confections were popular on two continents.

In the 1700s Cuffee Cockroach was a celebrated cook in the Jahleel Breton household, and the first caterer in Newport. His food nourished a large family of wealthy merchant traders and their servants. For many years, the family hosted a “turtle frolic” on Goat Island to celebrate the winter solstice. Hundreds of people came to the festive event; Cockroach’s sea turtle stew was a delicious attraction. It was served with the family’s finest silver and porcelain, brought to the island by boat.

Slavery in New England began to fade out by the end of the 18th century. Men like George Thomas Downing and Thomas George Williams were able to build thriving restaurant and hospitality businesses. Their business skills brought them financial success but that success didn’t turn their heads. They did not care about integrating into white society; instead they worked to maintain and lift up members of their black community—actions that were unique to Rhode Island, said Stokes.

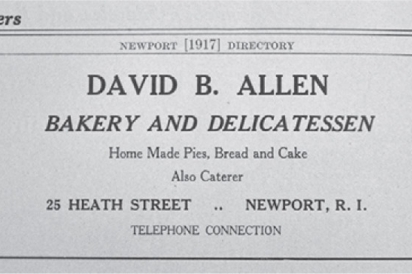

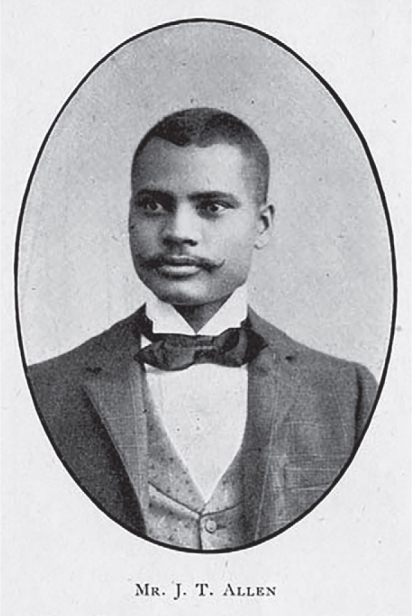

In the 1890s the Allen brothers—J.T. and David—arrived in Newport to establish the Hygeia Spa at Easton’s Beach and a high-end restaurant in the historic Perry Mansion at 29 Touro Street.

The admirable George Downing followed his father into the restaurant and catering business in New York City, and from there, followed his society clientele to Newport, where they were colonizing Bellevue Avenue with gilded summer “cottages.”

His restaurants at 27 Matthewson Street in Providence and the Oyster House Restaurant and Confectionary in the Sea Girt Luxury Hotel on the Downing Block in Newport were considered among the finest dining rooms in the country.

Downing’s real passion was social justice for African Americans. He fought to desegregate public schools in Rhode Island and, amazingly for the time, worked to repeal the ban on interracial marriage in the state. His contemporary, Thomas Williams, established restaurants in Boston, on College Hill in Providence and on Bellevue Avenue in Newport. The men worked together for the civil and political rights of African Americans throughout the 19th century.

When Downing died in 1903, the Boston Globe wrote of him, “The foremost colored man in this country expired in the person of George T. Downing.” A fitting tribute, but the culinary artists who preceded him probably deserved the same.

RelishingRI is a year-long celebration of Rhode Island culinary history. The Rhode Island Historical Society, the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, Providence Public Library, Rhode Island Latino Arts, the Tomaquag Museum and other institutions are collaborating to make sure “that everyone has a place at this table.” For information on upcoming programs visit RIHS.org/relishing-rhode-island-2017/ or call 401.331.8575.