Visionary Marc Harrison

He Imagined, and Created, Tools for a Better Life for Everyone

Marc Harrison (1936–1998) was a designer before his time. He was a humble visionary and gifted teacher whose influence shaped the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Industrial Design program as a faculty member and department chair.

Harrison’s entryway into a career in design was unusual. A childhood sledding accident at the age of 11 left him with brain damage and in need of extensive rehabilitation to relearn basic functions of walking and talking. During that period, Harrison felt that his world was hard to access. Without fully functioning motor skills, he couldn’t engage with his environment in the way that others did and he learned to feel different. In this space of difference, and as a young resident of New York City, Harrison spent much of his rehab years wandering around museums and galleries, letting the elements of art and design settle into the recesses of the brain he was re-creating.

Harrison’s design philosophy was born from this dynamic. As he pursued a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in industrial design from Pratt University in 1958 and a Master of Fine Arts from Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1959, he was drawn towards designing products for all beings, not just those of average size and ability, and not those with physical limitations as he had experienced—but for everyone, at the same time. This philosophy would come to be known as universal design.

Following graduate school, Harrison took a teaching job at RISD, where he would remain for the rest of his career while also operating his own design firm, Marc Harrison Associates. The projects he worked on in both settings incorporated universal design concepts at every level. He was particularly drawn towards designing everyday products in this way, tackling the barriers and frustrations of limited access.

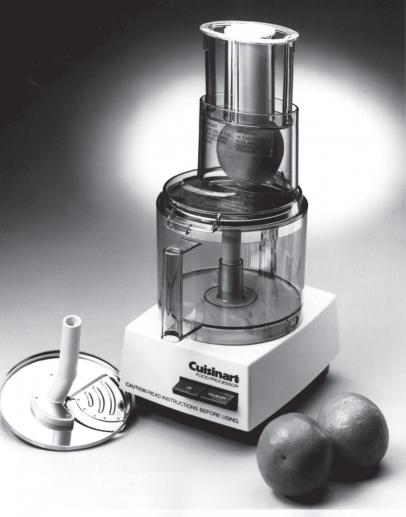

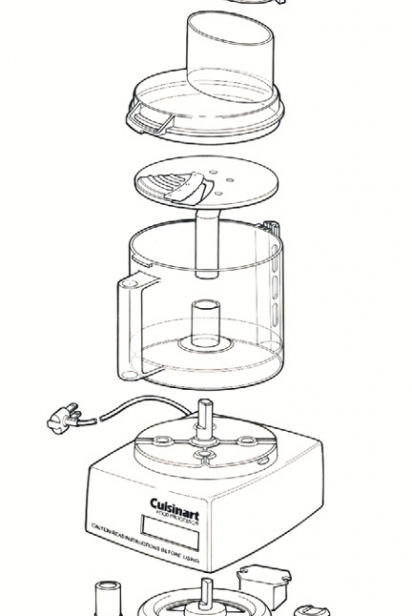

Perhaps Harrison’s most well-known design accomplishment was a now-iconic piece of kitchen equipment, the Cuisinart food processor. Harrison’s 1979 redesign of the existing machine was intended to meet the needs of a wide ranger of users. He incorporated large push buttons for “on” and “pulse,” in easy-to-read letters, and created large, easy-to-grasp handles.

The new design was a win for Cuisinart, making food processing an easy step for all cooks. “The Cuisinart was more like a research project for my dad,” says Harrison’s daughter, Natasha Harrison, of Newport. “He made a prototype for every single piece of the design elements and we would test them all at home at the dinner table. Every-thing had to be made at a high level but also be accessible.”

According to Cooks Illustrated, a magazine known for its tests and ratings of kitchen appliances, it is still the best-performing food processor on the market.

Harrison’s intense drive to research and problem solve was at the root of all of his design inspiration. This was his way to not only understand form and function, but to understand people and the way they move through their everyday lives. Natasha believes that this deep desire, stemming from that feeling of difference at a young age, was what ultimately fueled her father as a designer.

While the food processor design was a clear high point in Harrison’s career, many people—Natasha included—give equally high praise to his Cuisinart Grand Griddle, a small circular griddle that is famous for staying hot for hours. The Grand Griddle can still be purchased on eBay and evokes happy memories for its pancake-making fan base.

In 1993, late in Harrison’s RISD career, he helped take the universal design concept to another level with the Universal Kitchen, a project that engaged students, faculty and an active board of advisors, including Julia Child. The kitchen, the central place of work in a home, was the ideal space to problem solve and rethink traditional design.

“RISD was up for anything in those days and Marc was a magnet for people and ideas,” says Mickey Ackerman, former chair of the industrial design department and a current RISD faculty member. The project took off under the direction of interior architecture associate professor Jane Langmuir as the project leader and corporate sponsorship for funding. She began developing the idea in 1990. “We all start our day in the kitchen,” Langmuir says. “This seemed to me an imperative thing to tackle.”

In many ways, the traditional kitchen is made up of a series of disjointed design elements creating excess work and uncomfortable movements for the cook.

The goal of the Universal Kitchen was to dismantle these patterns and reconstruct the space in a way so that more people, of all shapes, sizes, ages and levels of mobility, could work independently and in harmony with each other.

The project began by considering the basic necessities of the kitchen—fire, water, surface and storage—and designing elements that worked for everybody. Each component was adjusted to meet the “comfort zone” of the individual cook, creating maximum ease and enjoyment, and for multiple users to work at the same time.

Components included surfaces that pulled out, dishwashers that popped up and recessed when running, continuous wet surfaces, multiple washing areas, a counter-height oven with a sliding door, interchangeable components and a self-contained unit where a meal could be created sitting down or standing up.

“Marc was a real leader in teaching his students to be innovators,” says Langmuir. “This was not surface design … we were getting at the core of the idea.”

A truly bittersweet detail of the Universal Kitchen story was that while Harrison was working on this tremendous project he was simultaneously battling ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease). While his own mobility was challenged more and more, he was able to engage authentically in his work. “And he did it without a diminished spirit,” says Langmuir.

Harrison died in 1998. Today, his spirit lives on in the design minds of every RISD student and faculty member who worked with him and the thousands and thousands of cooks who regularly use the Cuisinart food processor.