Whence Came the Rhode Island Food Truck?

One Appetizing Idea, Endless Permutations

The explosion of food truck culture over the past decade or so has been truly phenomenal. The wave came on so suddenly and spread so widely that one may be forgiven for believing the trend is utterly new. But today’s food trucks are part of a tradition of mobile food preparation that goes back centuries, if not millennia.

Here in Rhode Island, we like to trace that tradition back to a gentleman named Walter Scott. In 1872 he noticed there were a great number of night shift workers downtown who had grumbling bellies and money to spend—but nowhere to spend it because the restaurants and lunch rooms were closed. So he got an old covered horse-drawn freight wagon, cut windows in the sides, and began selling sandwiches, boiled eggs, pies and coffee outside the old Providence Journal building on Westminster Street.

Scott is generally credited by historians (and not just those in Rhode Island) as the originator of the diner. Richard Gutman, director of the Culinary Arts Museum at Johnson & Wales University, says he likes Scott as the starting point of the diner because the last remaining classic diner manufacturer, DeRaffele of New Jersey, can be traced directly back to Scott through documented business relationships and connections.

Historians are not so much in agreement that Scott was also the originator of the modern food truck. That’s because there are many other possible precedents in portable food stalls, carts and wagons going back through time.

On our own shores, the town of New Amsterdam (New York City) began regulating food cart vendors as early as 1691, and in Japan records show portable food stalls called yatai were selling ramen and other types of easily prepared foods in 1710. Trains began to feature dining cars in the 1850s, and, of course, there was the chuck wagon, which would seem to be an obvious precursor of the food truck.

Invented in 1866 by Texas Ranger Charles Goodnight, the first chuck wagon was a converted U.S. Army wagon stocked with everything needed to serve hungry settlers or cattlemen on a weeks-or months-long drive across the plains—including cooking equipment, utensils, tableware, spices, water, firewood and provisions like coffee, cornmeal, beans and preserved meat.

It was into this era of dining cars and chuck wagons that Walter Scott’s “Pioneer Lunch” wagon rolled out. By 1877, Scott’s idea had proved its worth, and thereby gained its share of imitators.

A man named Sam Jones introduced his own innovation that same year in Worcester, Massachusetts—a wagon with space for patrons to come in out of the weather. And it was only a few years later when former lunch counter employee Thomas H. Buckley began manufacturing custom lunch carts in Worcester to meet demand.

Buckley made his lunch carts classy—with names like The Owl, White House Café, and Tile Wagon—including intricate paint jobs, colored glass windows, silver carriage lamps, tile mosaics and other ornamentation, as well as sinks, refrigerators and cooking stoves. When Haven Brothers started business in 1893 at the corner of Dorrance and Washington streets in Providence, their first lunch cart was a White House Café, made by Buckley.

What kind of food could you get at one of these early, horse-drawn food trucks? The Star Lunch cart in New Bedford, Massachusetts, offered the following for five or 10 cents in the 1890s: hot frankforts [sic]; sliced or chopped ham sandwiches; sardine, cheese or chicken sandwiches; baked beans; clam chowder; pies of all kinds; boiled eggs; coffee or chocolate; and iced milk and tonics.

In 1906 Haven Brothers upgraded their wagon to a model made by another Worcester manufacturer, Wilfred Barriere. The same year saw the opening of the Worcester Lunch Car & Carriage Manufacturing Company, which utilized many former Buckley craftsmen. Primarily known for their lunch cars and diners, of which they would build hundreds over the next 50 years, they also dabbled in custom food trucks.

By 1912, lunch carts in Providence had begun to take unfair advantage, often parking in one spot and remaining there both day and night. The Board of Police Commissioners therefore placed a ban on daytime lunch wagons in the city, ordering that these (in the words of the Providence Journal) “more or less picturesque institutions” must be hauled away each day by 10 am.

Also noted were some half-dozen “two frankfurts an’ cup o’ coffee for a nickel” wagons occupying the city market area “in the vicinity of Dyer, Canal and South Water streets.” None were listed by name, but Haven Brothers was one that likely had to follow the new ordinance, and to this day they maintain their dusk and dawn commutes to park aside City Hall.

Once horseless carriages became cheaper and more ubiquitous it was only a matter of time before the lunch wagon owners would trade in their horses for horsepower. World War I hastened the switchover, as the U.S. Army began using mobile canteens, or field kitchens, to feed the troops.

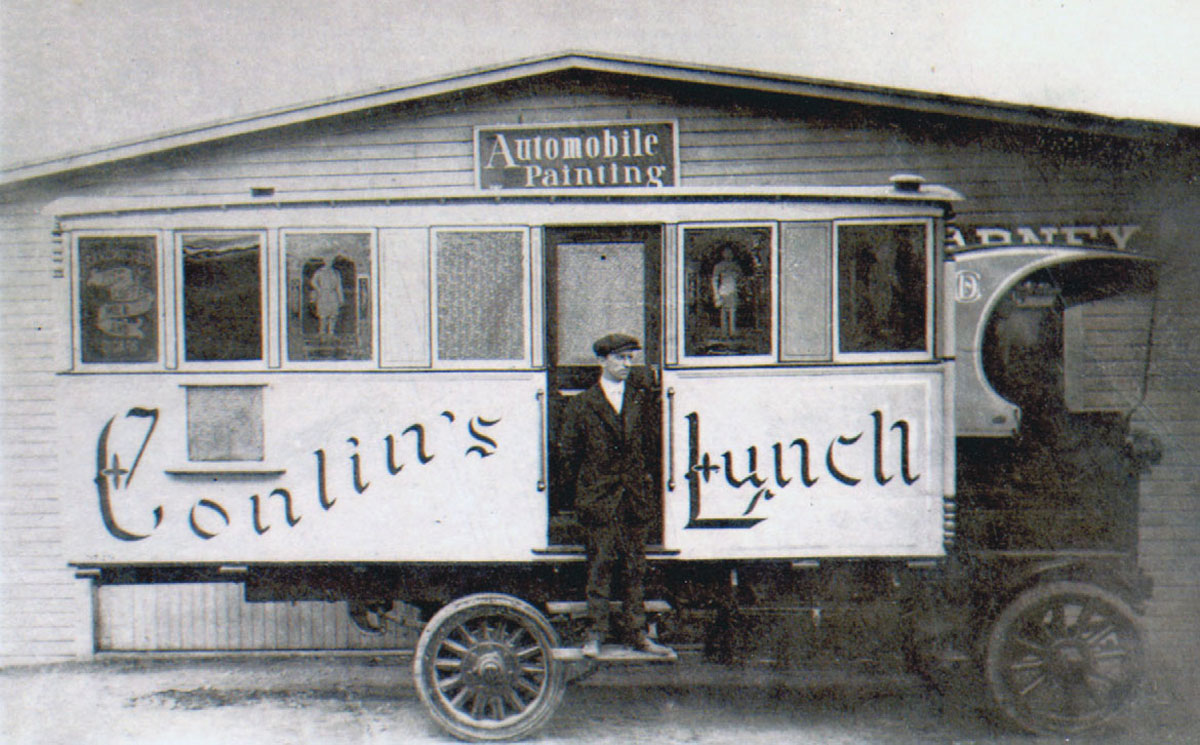

1918 seems to be the magic time for the marriage of lunch cart and truck in Rhode Island. That’s the year Daniel C. Conlin of Providence had Worcester Lunch Car #310 built on the back of a flatbed truck. Meanwhile, James Isaac Barker parked his motorized White House Café in Newport’s Washington Square, following in the footsteps of longtime food cart vendor “Peanut Joe.” While some lunch wagons in Taunton, Massachusetts, were still horse-drawn as late as 1938, the era of hay-fueled transport was drawing to a close.

The 1927 Providence City Directory lists four lunch carts in Providence, two in Central Falls, three in Newport, one in Pawtucket and six in Woonsocket, plus innumerable establishments with “lunch” in their name that may or may not have been mobile.

Various kinds of food trucks proliferated in the 1930s, as “novelty trucks selling ice cream, hot waffles, and other unique treats began to roam the streets of cities and rural communities.” Some grocery stores began using trucks to deliver door to door, like an early version of Peapod. In 1936 Oscar Mayer injected some whimsy with their first portable hot dog cart, The Weiner Mobile.

A 1943 Providence Journal article detailed the consternation of city aldermen on discovering that Mike’s Diner had installed a permanent water hookup. Mike’s, a trailer located on the west highway approach to the old Union Station, had previously been towed into place each day, as required, but citing the need to ration gas and tires for the duration of the war, the diner requested and received at least some of the proper permits to make the water connection. Another, the Ever Ready Diner, had permanent water and sewer connections in their spot on Admiral and Charles for some time. City government subsequently decided it had set a bad precedent with Mike’s, rescinded permission for the water hookup and ordered the diner to resume its to-ing and fro-ing. The Ever Ready, already firmly entrenched, stayed put.

Post World War II, returning servicemen, many of whom learned the art of basic cooking in the military, took to running diners, food trucks and food carts, emulating the canteen trucks with which they had become familiar. On city streets, at construction sites, at festivals and fairs, parks and beaches, these mobile eateries sought out all the places where hungry people might congregate. And over the next couple of decades it was perhaps inevitable that some bad apples, lacking a commitment to high standards of cleanliness and freshness, would color the public’s perception of such establishments. Hence the stereotype of the “roach coach.”

The fortunes of food trucks have waxed and waned with the economy. When people were watching their money during the recessions of the early 1970s and ‘80s, food trucks, with their inexpensive menus, did well. In boom times, like the early ‘90s, food trucks struggled.

But the game changed in 2008. That was the year Kogi Korean BBQ broke out in Los Angeles. They broke the mold with a gourmet Asian-Mexican fusion menu—and by their use of the Internet and social media. Suddenly it was cool for top-end chefs to run a food truck on the side. Today’s trucks come in all shapes and sizes, sport colorful and elaborate “skins” and some even swapped chalkboard menus for flat-screen TVs.

In Seattle, Washington, the Maximus/Minimus food truck is shaped like a giant steel pig. On Mammoth Mountain in California, Roving Mammoth is a snowcat that feeds skiers. In Oxnard, California, the Space Shuttle Café is shaped like its name—made from a DC-3 fuselage. And right here in Providence, Julian’s rolled out their doubledecker omnibus, with a kitchen downstairs and “human” seating upstairs, in 2010.

Today there are more than 40 food trucks in Providence alone, serving everything from gourmet grilled cheese and crêpes to French, seafood, Portuguese, Italian, vegan, Chimi and Asian fusion cuisine. And as always, Haven Brothers endures.

It’s a far cry from boiled eggs and chopped ham sandwiches.

Christopher Martin is the curator of Quahog.org, a website about Rhode Island’s history and cultural quirks. His favorite food truck of the moment is actually a trailer, a hidden gem at 269 Greenville Ave. in Johnston.