Their Place or Yours?

Chefs Turn to Takeout in Tricky Times, with Mixed Success

Recently, I was craving a burger. I also found myself thinking about a specific burger, one I had admittedly not tried, yet. My craving was in part fueled by a conversation with friends a few days earlier, when one mentioned that she and her boyfriend had gotten takeout from Jo’s American Bistro on Memorial Boulevard in Newport. It was surprisingly good, she said, considering they had to drive it home, about 10 or 15 minutes across town.

I was intrigued. In pre-pandemic times, a conversation about takeout that surpassed expectations would probably have been non-existent, let alone of interest. Who ordered burgers to-go from sit-down restaurants a year ago? Not many people.

When my craving struck, I decided to call Jo’s and give the experience a whirl. I placed an order for their Bacon Onion Jam Burger, which features an all-natural ground beef patty, topped with Dijon, bacon onion jam, cheddar cheese and house-made special sauce, and is served with hand-cut fries and house-made pickles.

I was told it would take about 15 minutes, and confirmed it would come with fries and pickles; about five minutes later, I left my house and set off to collect my food. I was on foot, but should I have driven, a spot would have been waiting for me out front. I gave my name at the door, waited a few minutes curbside, and then was delivered my burger.

I quickly retraced my path home and, once in my kitchen, unpacked my meal, which was smartly packed: The burger was wrapped and nestled into a cupcake box, the top of which was stamped with, well, a burger; and the fries were in a familiar white and red to-go box, also wrapped in paper, which seemed to have absorbed most of the grease en route.

Without much ado—although I did put my burger on a plate (the fries I kept in their container)—I dove in. It was messy and juicy and tasty, all the signs of a good burger. The sauce and the bacon and the pickles all satisfied my craving. The bottom of the bun was a bit soggy, and the meat itself was more warm than hot, but I figured those are the sacrifices of walking it home and setting the table before diving in. The fries were plentiful and remained crispy (even the next day when I toasted the leftovers and enjoyed them with a soup I’d reheated).

It was an altogether enjoyable experience, and one that saved me from having to cook and clean up after yet another meal (while supporting a local eatery: a win-win), although I still prefer eating my burgers at a restaurant, and with company. They don’t quite taste the same when you’re alone in your kitchen, surrounded by the mess of everyday life. But so it goes in this prolonged season of Covid-19.

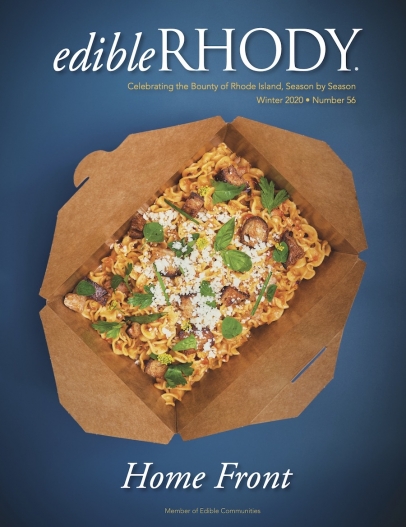

A few weeks later, I called Joann Carlson, the owner of Jo’s, to ask how the restaurant is adapting to takeout culture. Carlson descends from a family of restaurateurs and kitchen folk: Her grandparents ran a fish packing company in downtown Newport, and her family owned and operated Dry Dock Seafood on Thames Street for 23 years. She said it was her daughter’s idea to take inspiration from those seafood days to accommodate current to-go orders: All the food is placed in takeout containers one would find at a clam shack.

“We put a lot of care into our packaging,” Carlson said. Takeout in mid-October was averaging 40% of her business, up from 20% over the summer, a number she expected to increase as outdoor temperatures decreased.

The most popular items ordered to-go include burgers and fries, of which there are a few varieties, and the Lobster Carbonara (lobster, bacon, tomato, peas, Parmesan lobster cream sauce, served over spaghetti). Carlson is not including beer, wine or cocktails with to-go orders. To do that, she would have had to hire another bartender, which “economically, really wasn’t feasible for us,” she said.

Carlson has some customers who haven’t eaten out since lockdown began last March, but who continue to order via takeout twice a week. One such couple said to her in October: “See you when this is over.”

Not too far away in Exeter, Branden Read, chef/owner at Celestial Café, has slimmed down his menu to better suit takeout orders—and to-go packaging—including his beloved farm dinners, which continue to take place each month.

“The farm dinner is always something kind of exciting,” Read said. “That’s my fun time.”

Although, “I had to up our container game,” he said. “I’m super picky about keeping cold items cold, and hot items hot.”

Now, when customers order takeout, meals come with the sauce on the side— something that would never happen if they were dining-in. And some things, like the Eggplant Tower—formed of crispy panko fried eggplant, RI Mushroom Co.’s chef mix, tomatoes, Farmer Co-Op greens and other local veggies plus a pesto sauce—can’t be transported assembled, but Read sends people home with all the fixings and encourages them to re-create the tower in their own dining rooms.

When asked if he might close for a winter hibernation, Read said that he’s not going anywhere. “I’m going to be here cooking, no matter what.”

“A lot of people depend on us,” he continued, “the farmers, the fishermen.” To close, even for a few weeks, he said, would negatively affect the farmers who supply the restaurant’s eggs, microgreens, meats, oysters. “We need to keep our small farms making an income, too.” Read said, adding: “They’ve been good to us.”

Overall, Read said he’s “just playing it day by day,” expressing a sentiment echoed by many of his industry peers. “We’re trying not to lose, and not losing is winning right now.”

Ben Sukle, chef-owner of Oberlin in Providence, recently had to take one loss: the closure of Birch, a lauded 18-seat haute-cuisine restaurant, which he had run for seven-and-a-half years.

“I couldn’t survive with takeout at both restaurants,” Sukle said, noting Birch wasn’t suited to pivot in that direction.

At Oberlin, where house-made pasta has always been a to-go option, there’s been increased demand for baked goods, and Sukle plans to build up his pantry items accordingly with the winter season. Among the most popular breads are the focaccia, sourdough, sandwich loaf and Portuguese-style dinner rolls.

Other favorite to-go items include the Mafalda Corta, a pasta named after the wide noodle with frilly edges that is served with tuna conserva, capers, tomato pesto and breadcrumbs; and Pasta e Fagioli—”our take on pasta fagioli,” Sukle said—with fresh Borlotti beans, Habanada peppers, bitter greens and rich roasted chicken broth. Another favorite includes pizza on Monday nights, served Sicilian- style and formed of a sourdough crust that is “really lovely and fluffy.”

Food orders made to go are prepared somewhat differently at Oberlin. For instance, sauces are made looser, pastas cooked for less time so they end up the right consistency when people arrive home 20 or 30 minutes later. The same sauces are also served on the side. For fish dishes, the lemon and salt come on the side, too. “We want the fish to travel well,” Sukle said.

Other adjustments to the menu include reducing the prices of beer and wine, which, along with craft cocktails, are available to go, to reflect costs more common in package stores. “There’s a reckoning that’s happening with all of this, in my mind, with how we do pricing on food versus alcohol and the markups that traditionally go witheach,” Sukle said. He has also eliminated tipping wages for his staff, all of whom make an hourly rate above minimum wage. Any tips collected are divided between the front and back of the house.

Sukle expects to close Oberlin for a bit of a break this winter.

“I like to think things could be better, or could be worse,” Sukle said. “We all just want to fast-forward to April.”

For Aaron DeRego, the chef/owner of The Red Dory in Tiverton, which he bought from the previous chef/owner, Steve Johnson, in 2019, takeout has allowed his restaurant to remain operational, especially in the spring, before onsite dining was an option. “It’s still a fraction of what we would do under normal circumstances, but it was something. It allowed me to keep my salaried people on staff,” DeRego said. Since the return of indoor dining, albeit at limited capacity, he figures takeout accounts for about 20% of overall food orders, a number that could increase this winter.

“All my big costs are the same,” DeRego said of running the restaurant. “To limit what I could normally do to takeout … It’s only a matter of time until I can’t make it work.” He hopes winter sees the continuation of in-person dining, but like his peers, DeRego is really focusing on one day, one week, at a time.

“I’m not trying to look too far ahead,” he said, which means continuing to serve his regulars the dishes they love, which has involved a lot of soups to-go, like the smoked haddock and clam chowder, and the butternut squash soup with pepitas and smoked paprika.

DeRego plans to stay open for the winter. “If I’m forced to close, at least I didn’t voluntarily close,” he said. “I’d rather make the choice than have someone make the choice for me.”