Farmers Put Down Roots in City Plots

A Story of Sweat, Equity and Perseverance

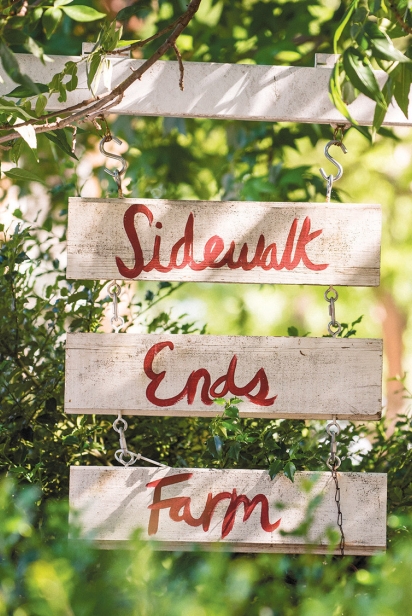

When I think of a farm, I picture a bucolic landscape of greens growing in straight lines over acres of dark soil. It’s not like that at Sidewalk Ends Farm.

Last summer the commercial farm on the West Side of Providence and a companion plot in Seekonk, Massachusetts, produced enough food and flowers to supply 55 community-supported agriculture (CSA) subscribers and two weekly farmers’ markets. This bountiful harvest was planted and nurtured by three young women (one age 28 and two are 29) on a 5,000-square-foot lot on Harrison Street and two acres in Seekonk.

Sisters Tess and Laura Brown-Lavoie began their urban farm with two friends in 2011 in the city’s Armory neighborhood. They grew up in Brookline, an upscale suburb of Boston, surrounded by lawns and flower beds. But during a semester abroad while attending Brown University, Laura worked on an organic farm in France and discovered that she liked the physical rigor of farming. Tess, a graduate of New York University with a degree in literature, joined her for more holistic reasons. New York City is hard-edged and fast-paced—not hospitable to someone looking for a more down-to-earth lifestyle. Laura wanted to be close to “systems that make life possible.”

Sarah Turkus and Fay Strongin, Laura’s “best friend since first grade,” completed the farm quartet; Fay left for graduate school at the end of the 2015 growing season.

How do the partners divvy up the farm work? Most decisions are made by consensus, but each has a particular responsibility. Tess is in charge of buildings and infrastructure, Sarah Turkus takes care of the flower beds, Laura does crop planning and composting. There is outreach to local restaurants, tours for student groups, maintaining an elegant website, serving CSA customers in three locations and selling at the Armory Park Farmers’ Market in Providence and the Weaver Library Farmers’ Market in East Providence.

As for day-to-day chores, “We each take on daily odious jobs as they come up,” says Laura. But it’s not all weeding and hoeing. “We’re a farm that believes in weekends,” says Tess. Away from the farm, she is a drummer in Mother Tongue and has toured the West Coast with the rock band. Laura’s nonfarm passion is poetry. “It’s where I process what’s going around in my head. It helps me express my feelings about the world around me.” She loves to mentor young high school poets.

“Agriculture is constantly humbling,” says Tess. In the beginning they made lots of mistakes—in deciding what crops to grow, learning about government regulations and how to package and deliver their products. She describes hauling produce to the Armory Park Farmers’ Market in a bicycle cart that first year. “We were idiots,” she admits. They learned how to farm through trial and error and from established farmers who generously shared their knowledge.

Now, Tess is also working for Land for Good and has served on the boards of local organizations like the New England Farmers Union, the Rhode Island Food Policy Council and the Rhode Island Agricultural

Partnership. Sarah organizes the Young Farmer Network and serves on the board of Northeast Organic Farming Association of Rhode Island.

There are more than 20 city-owned lots in Providence that could be farmed, but urban agriculture has unique challenges, says Yesim Sungu-Eryilmaz, an instructor in the Urban Studies Program at Brown with a special interest in sustainable cities. For one thing, the ground is often contaminated with lead. It took lots of backbreaking work to get the Harrison Street plot ready to farm that first year. On the back half of the litter-strewn lot, the women dug out three inches of compacted soil with hand tools. Raised beds were built from lumber found around the city and filled with truckloads of compost. The soil and produce are tested every year for contaminants.

And after all that hard work, would-be urban farmers face the prospect of losing their land if the owner decides that it’s time to sell for a profit. Sidewalk Ends Farm began on a vacant lot filled with weeds and trash. A house on the property burned down sometime in the 1980s. The absentee owner lives in Buffalo, New York, and has been out of touch for years. Laura and Tess agree that land insecurity (the threat of losing the use of the property) is a real problem. So far, they’ve been lucky, though they have only a verbal agreement with the owner.

But that was not the case for Nathaniel “Than” Wood. In 2009, Than began Front Step Farm at 1240 Westminster Street, where he grew produce for sale in raised beds that he filled with compost and seaweed. After two successful years and after he built a greenhouse and prepared the beds for a third season, his farm was unceremoniously shut down and the land sold to a nearby nonprofit agency.

The city offered Than an abandoned parking lot on Almy and Slocum streets, a spot that would challenge the most experienced farmer, but undaunted, he again built raised beds on the concrete and filled them with 75 cubic yards of compost.

Lack of water and a colony of hungry groundhogs provided challenges at his third location—a small plot at the intersection of Bowdoin and Amherst streets in Olneyville—where he currently grows a variety of fruit trees.

Looking back, Than calls his negotiations with the nonprofit “one of the most unpleasant conversations I’ve ever had.” He loved farming in front of a bus stop and talking to people who walked by. Despite his financially and emotionally draining experiences, Than says he’s been lucky to work with many passionate farmers in Rhode Island. He’s also happy that his first two locations have remained as gardens, just gardens with different missions.

An opportunity arose and Than left for a spell to try urban farming in San Francisco. The good news? He returned to Rhode Island and, in the spring of 2016, started Foggy Notion Farm, located within Snake Den Farm in Johnston, with Adam Graffunder, another urban farmer.

More and more people are living in cities and often urban planners don’t see farm plots as the best use of land. But like city parks, a neighborhood farm has social and environmental benefits, especially in rundown neighborhoods, says Sungu-Eryilmaz. Southside Community Land Trust (SCLT) has improved the neighborhood around Somerset and Dudley streets, says Rich Pederson, city farm steward. In 1981, concerned citizens turned the two-acre property, which had become a graveyard for junked household goods, into plots for growing food—and the nonprofit land trust was born. Now, 350 community gardeners grow food in SCLT’s numerous community gardens for themselves or to sell, and the Dudley Street garden is mainly a production and demonstration farm.

The women of Sidewalk Ends Farm appreciate the human scale of agriculture pioneered by SCLT. Though they have a tractor purchased on Craigslist, they still try to do most of the farm work by hand. Sitting on a tractor in the sun all day doesn’t appeal to them.

They want to grow food using as little nonrenewable fuel as possible.

After six years, the soil on their city plot is much improved and the women plan to increase production this year. “Having clean, healthy local food shouldn’t be a privilege; it should be freely available,” says Tess.

Some of their Harrison Street neighbors were not pleased when the women began digging, but now they are friendly and supportive, says Laura. One woman helped Tess plant husk cherries, which she remembered from her native Cambodia. Another neighbor helped rebuild a fence that was knocked down in a storm. There is a community compost pile at one end of the property. People often stop by to visit a flock of chickens kept on the property in a coop that Tess built. “We eat the eggs,” says Laura. “We only have five chickens and we’re three hungry girls.”

To find out more about Sidewalk Ends Farm, visit: SidewalkEndsFarm.com.

To find out more about urban agriculture in Providence, visit: SouthsideCLT.org.