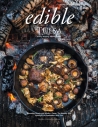

Mole Poblano at El Rancho Grande

A Little Bit of Chocolate and a Whole Lotta Love Go into Chef and Restaurateur Maria Meza’s Authentic Mexican Dish

Since Maria Meza, chef and co-owner of El Rancho Grande, is a native of Puebla, Mexico, she has good bragging rights for her recipe for mole (pronounced “MOH-lay”) poblano.

Though there is still some debate over the origin of this dish, the most oft-told legend is that the nuns at the Convent of Santa Rosa in Puebla were scrambling to find a way to make a special sauce for the visiting archbishop. They threw together some dayold breadcrumbs, dried peppers, ground nuts and a little bit of chocolate and served the mole poblano sauce over roasted turkey.

Indeed, “mole” means “ground-up,” related to “molino,” a mill or grinder, explains Joaquin Meza, bar manager and co-owner with his mother at the restaurant. Thus, in San Pedro Atocpan, where a mole festival takes place each October, there are four basic moles sold as pastes: poblano, pepian (with pumpkin seeds), verde (with tomatillos and fresh herbs) and roja (tomatoes along with ground nuts).

A mole festival in Los Angeles this fall offered 13 variations; four are served at the dozens of Richard Sandoval Mexican restaurants around the globe. And the other traditional place in Mexico for moles is Oaxaca, where Maria’s mother was from and which Maria visited often as a child. There are said to be at least seven basic mole sauces that came out of Oaxaca, many of which do not use chocolate, which Americans have linked inextricably with mole. Maria mentions a mole negro from Oaxaca, made only with pasilla peppers, which are black when dried.

“It’s an old-school way of cooking there,” Joaquin emphasizes, as I talk with him and Maria over steaming cups of “hot chocolate,” one made with water and one with milk (more on this later). “They kept their indigenous foods, whereas in Puebla, the colonial influence is felt a lot more.”

“People in Puebla make mole sauce spicier,” Maria adds. “Mole poblano is sweet and spicy.”

Indeed, Maria’s recipe has a total of 20 ingredients, and, from her description of different Oaxacan moles, her recipe seems to include some typical Oaxacan ingredients as well as those often listed for mole poblano. It includes three dried peppers—ancho (the red version of poblano peppers), pasilla and mulato (brown when dried and also related to poblanos)—plus the dried bread, the ground nuts and sesame seeds; the sweet and savory spices; and even raisins and ripe plantains.

As for the chocolate, Maria recommends the Ibarra or Abuelita brands, which come in packages of hexagonal or round tablets. (Both can be found in well-stocked supermarkets and Latino grocery stores.) But it’s my good fortune that her aunt has just sent a hefty wedge of “homemade chocolate,” which she brings out for me to taste (and for Joaquin to eagerly slice small chunks to snack on). This is made from roasting cocoa beans, rubbing off the skins and grinding them with sugar and cinnamon.

This can be done in a food processor, but the cocoa butter is likely to separate and not hold it all together (and can put the engine to the test). Traditionally, a warmed mortar and pestle are used to grind the beans, sugar and cinnamon together until the mixture looks satiny.

“My mother used to make the chocolate,” Maria remembers, her hands making the grinding motions. “And then she would mold it in tiny baskets. She used more cinnamon with the chocolate than commercial chocolate-makers do.”

“And they used to make a ceremony out of preparing the hot chocolate drink,” she remembers. “Instead of coffee, the typical drink in Oaxaca is hot chocolate, and they even drink it cold in the summer.”

Maria has fond memories of that warm chocolate drink with bread dipped into it, and she has passed this treat on to her children and grandchildren. My own comparison of the chocolate drinks made with water and with milk is that the latter is definitely less “fudgy” (more like “milk chocolate,” after all) but the former could be too strong for some sippers. The cinnamon definitely comes through more in the water-based version.

“In Chiapas, they still use that ‘homemade chocolate’ to make a spicy water-based chocolate drink, with hot peppers, that you can buy on the roadside,” Joaquin notes. “There’s also a chocolate atole [corn-based drink]. They make the chocolate drink and atole separate and pour them from a height to get a froth.”

But whether the chocolate is “homemade” or store-bought, it is still a crucial ingredient for mole poblano sauce as well as the beloved hot drink. Many Mexicans buy the sauce as a jarred “paste” and thin it with broth. Joaquin is in an entrepreneurship class from Cornell University online so that El Rancho Grande can soon bottle and sell its own mole poblano sauce.

For now, it’s enough to just dig into a plate of Maria’s rich and delectable mole poblano chicken (and on special occasions, turkey). First scoop some onto a warm tortilla or put a bit onto a forkful of rice. Or, finally, settle in for a bite of chicken with 20 spices, herbs and chocolate doing a Mexican hat dance on your taste buds! Olé.

El Rancho Grande

311 Plainfield St., Providence, RI 401.275.0808; ElRanchoGrandeRestaurant.com