Food Policy Tops the Menu at Rhody Summit

Rhode Island’s first-ever Food Policy Summit pulled together 350 local food producers, policy makers, chefs, fishers, food distributors, institutional buyers and other stakeholders in the local food community to roll out the initial draft of the Rhode Island Food Strategy, a five-year food action plan for our state. The January 17, 2017, event was held at University of Rhode Island’s Center for Biotechnology and Life Sciences on the Kingston campus.

The R.I. Department of Environmental Management, the R.I. Food Policy Council and the R.I. Department of Health organized the summit. Other sponsors included Farm Fresh Rhode Island, Edible Rhody, Main Street Resources, Eat Drink RI and the Henry P. Kendall Foundation.

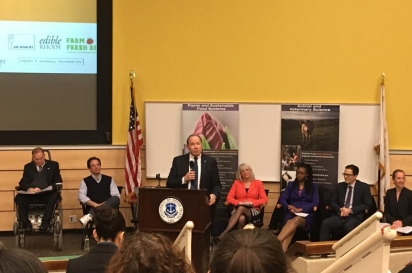

The day kicked off with a welcome from state Director of Food Strategy Sue AnderBois, who laid out the goals for the day and touched on the main sectors of the food strategy which together make up the core components of the local food system: Agriculture and Fisheries; Economic Development; Health and Access.

In his introductory remarks, First Gentleman Andy Moffit said, “Food is an essential part of Rhode Island,” in reference to its identity and its economy.

Dr. David Dooley, president of the University of Rhode Island, and Congressman Jim Langevin spoke, as did Janet Coit, director of the R.I. Department of Environmental Management.

“Rhode Island leads the nation in direct sales [from farm to consumer],” said Coit. “We are near the top in the number of female-owned farms. Our successful LASA grant program provides $400,000 in seed money to help farmers and producers.” She praised Governor Raimondo for her leadership in appointing the first director of food strategy to develop the first statewide food strategy study in the United States.

Next came R.I. Department of Health Director Dr. Nicole Alexander-Scott, who said, “Governor Raimondo has challenged us to address the underlying issues like food insecurity and access.”

Short keynotes representing the various sectors of the food community included a chef and food activist, a farmer, a hunger activist, and the owner of a food business start-up. Dave Beutel, of Coastal Resources Management, underscored the theme of the day when he said, “If it’s grown in Rhode Island—you ought to eat it. If it’s caught in Rhode Island—you ought eat it.”

After a locally sourced lunch prepared by university culinary staff, participants chose from 10 breakout sessions to “tackle critical issues affecting the development of a sustainable, equitable food system in Rhode Island—including mapping funding and training opportunities for farm and food businesses, navigating regulatory burdens for new ventures and addressing food insecurity across the state.”

The afternoon’s first session, “Early Wins & Opportunities,” included: Mapping Financial Resources for Food Enterprises; Connecting Rhode Island Food Producers & Institutions; Technical Assistance for Farm, Fisheries & Food Businesses; and Waste Not, Want Not—Diverting Food Waste to Rhode Islanders.

Rhode Island Food Policy Council’s Leo Pollock moderated three tabletop discussions for the session titled Sustaining Local Food Businesses: Balancing Scale & Growth.

Of these tabletop hosts, Pollock said, “These are people turning vision into reality. We love to celebrate small businesses and talk about ‘hot’ chefs, but … I want to highlight what this really looks like—growing a business … local sourcing, building relationships and being part of growing that food system overall.”

William Bigelow of Blount Fine Foods, Mike Reppucci of Sons of Liberty Spirits Company and Mark Federico of Narragansett Creamery were the hosts for one table.

Referring to his business, Reppucci claimed he had been “just smart enough to pull it off.” When he didn’t know how to make whiskey, he called Maker’s Mark distillery, which offered him help through its new consulting program. When he didn’t know how to bottle his product, he called a Rhode Island manufacturing company owner, Karl Wadensten, who lent Reppucci a manufacturing consultant for six weeks.

“I don’t know why people are so generous, but if you have passion and you have a problem, call,” said Reppucci, who knew neither Wadensten nor anyone at the Maker’s Mark distillery when he sought help. “In Rhode Island … you’ll be shocked by how many people will help you.”

Rhode Island is lucky to have Hope & Main, and networking with others in the industry is helpful, agreed Bigelow, who finds that making the food product is far simpler than are the distribution and retail operations. Of Blount’s decision to expand nationally by buying a company that makes frozen entrées, which it is now selling, Bigelow said, “As you continue to grow, you can’t be all things to all people. Invest in what you know. If you branch out [and] do your research … you could still be wrong.”

Determining how quickly to grow is a tough balancing act, said Federico. Narragansett Creamery focuses on slow, planned, organic growth and builds demand through word-of-mouth and farmers’ markets before going further. People wanted nutritionally good food with no preservatives; they created the want and we helped fulfill it, said Federico, in describing the company’s decision to make yogurt.

Local food producers face very low barriers to get their products into locally owned grocers, such as Dave’s Marketplace, Clements’ Marketplace and Belmont Market, which like to feature local goods, said Bigelow.

With 33 new breweries opening this year in Massachusetts, Reppucci wonders about his decision to open a brewery. Nevertheless, he finds that more competition drives him to focus and specialize in a niche market. “Don’t go for the mass market [garbage]; volumes are lower [for a niche product], but consumers want to taste it.”

In closing, they all seek customer feedback on products in development. Federico learns a great deal from people at farmers’ markets and Reppucci from industry experts. Federico warns against getting complacent and Reppucci advises people to avoid over-thinking everything.

Representatives from Indie Growers, The Backyard Food Company and RI Mushroom Company hosted one discussion; representatives from Easy Entertaining, north and Matunuck Oyster Bar hosted another.

The afternoon’s second session, “Growing Local Food,” included Regulatory Challenges for Food Enterprises; Understanding & Growing the Commercial Fishing Industry; Crafting a Vision for Local Agriculture; and Relish Rhody: How We Talk About Food in Rhode Island.

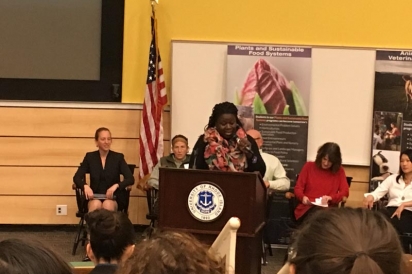

“Food doesn’t live in a silo,” said Olivia Kachingwe, who works for the Newport Health Equity Zone. The cost of food, child care and transportation coupled with working one or more low-income jobs, having insufficient time to prepare healthy meals and lacking cooking and budgeting skills are barriers to choosing, preparing and consuming healthy foods, she said.

Kachingwe, who holds a master’s of public health from Brown University, was one of several speakers in the session titled Getting to the Root Causes of Food Insecurity in Rhode Island. Getting at those root causes is a complex, multi-layered challenge, and one that won’t be solved overnight, presenters agreed.

That Rhode Island was the first state in the nation to hire a director of food strategy (Sue AnderBois) is “amazing,” said Eliza Cohen, food access coordinator at the Rhode Island Public Health Institute, which coordinates Food on the Move, a mobile market providing fresh produce to individuals and families who might not otherwise be able to access them.

In lively discussions—and occasional debates—audience members and presenters wrestled with a host of issues: How do we get enough food to those relying exclusively on SNAP benefits (formerly called food stamps), which are intended to be a supplementary source of nutrition? How can we persuade people that cooking with whole grains and dried beans is a nutritious and inexpensive, albeit more time-consuming, approach? How do we solve the transportation barriers that keep many low-income people from accessing fresh and healthy foods at a full-service grocery store, who may otherwise buy less-healthy foods at bodegas or convenience stores?

Food insecurity—where people go to bed hungry, skip meals out of necessity, have insufficient funds to buy food and worry about not having enough—is a real problem, and one affecting about one in every eight households in Rhode Island. The state’s 12% rate of food insecurity is “not inevitable; we can feed people,” said Cohen, who seeks to eliminate the false dichotomies associated with healthy foods and addressing hunger. “We have a real opportunity to come together with creative solutions, concrete ideas and grassroots power to get beyond tradeoffs. We can have viable farm economies and food security for all Rhode Islanders.”

Food access from an eater’s perspective, food insecurity variations across the state, social disparities in food access, how to build high-quality neighborhood food environments, fighting the tradeoffs between hunger and health and policy goals for state and federal governments are among the “big problems” associated with resolving food insecurity, said Cohen.

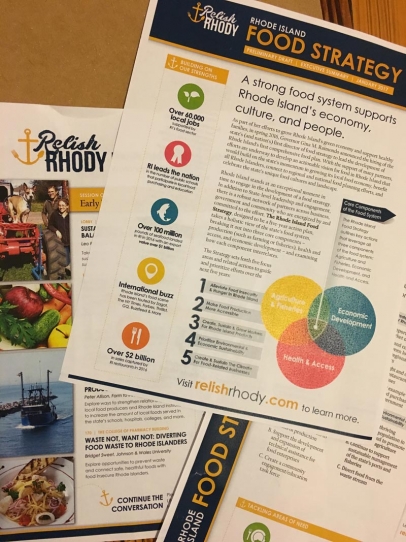

To read an executive summary of the Rhode Islands Food Strategy or the preliminary draft, visit RelishRhody.com.